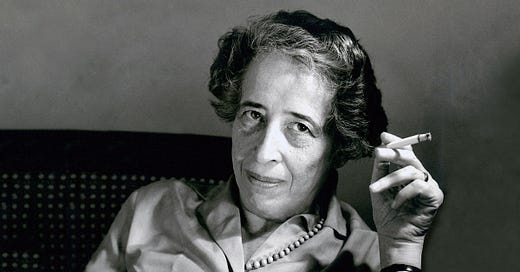

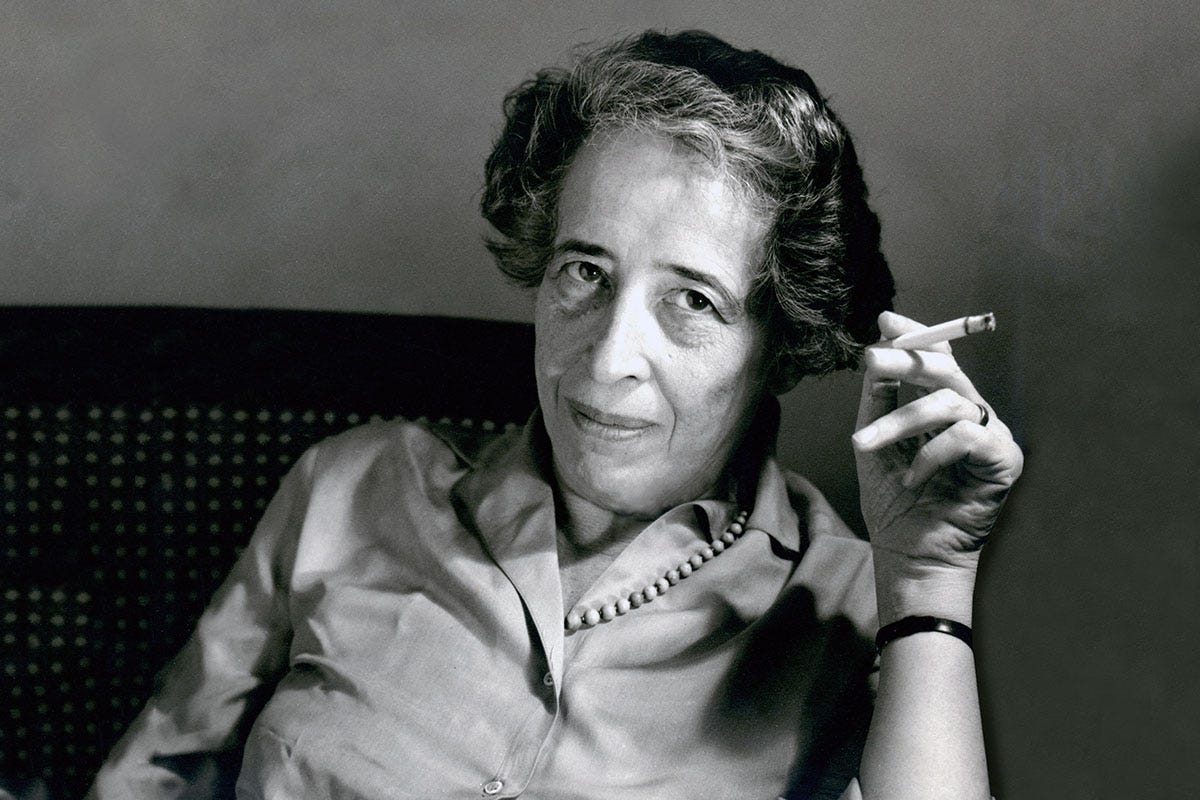

The following is an experiment. A form of thinking out loud. It takes quotes from my recent reading of Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism (1950; rev. ed. (1966;1967) and records my reactions to her contentions. A sort of reader-response paper that a college professor might require of a student, only with a lot more words than any prof would ever want to read from a student paper. The reason for my quoting Arendt at length is that I doubt that many of those who might read this are deeply familiar with Arendt’s book, or at least haven’t re-visited it recently enough to know what might have spurred my thoughts and reactions. I’m in the midst of re-reading this work as a participant in the Virtual Reading Group of the Hannah Arendt Center at Bard College, led by Professor Roger Berkowitz. Before this, I probably read it in full last in about 1977 or 1978—a long time ago. And things were different then. We’d seen Richard Nixon capitulate to the rule of law and the mandates of the Consitution.

And we didn’t have Donald Trump.

George Wallace, yes, but he was never a threat to win the presidency, and no one since then has so openly and brazenly flaunted Constitutional mandates and norms. Lots of thin arguments and fig leaves, but no outright defiance, no shocking grabs at power.

Until Trump.

Of course, Trump is nothing without his zealots. What makes them tick? What does he have that so attracts his supporters? What traits, what words, what performances, what slogans, what gestures? What beliefs, fears, desires, and resentments do his followers hold? Of course, there are also office and power-seekers, his minions, his toadies, that surround him and serve him, but they are relatively few, and their motivations—power, acclaim, wealth, and cowardice—are all too easy to discern.

Trump remains almost certain—barring jail or a sudden failure of his health—to be selected as the next Republican nominee for president. His 91 felony indictments, his civil suits for fraud and defamation, and a judicial finding of rape (in the context of the civil trial) trail behind him as so much flotsam and jetsam in the wake of a seemingly invincible battleship.

Hannah Arendt, on the other hand, wrote this book about nineteenth and twentieth-century Europe, Nazi Germany, and Stalin’s Soviet Union. So what’s the connection?

When I read a text such as Origins, I focus on what the author is saying about her topic and what I’m learning (or confirming) about the subject about which she’s written. In short, I focus on the text and the author’s intention and evidence in promoting her thesis. In this particular chapter, entitled “A Classless Society,” I’m wondering what she will say about the conditions that gave rise to the prototypical totalitarian regimes of the twentieth century. But as I read this selection, my mind kept turning to what’s happening (and may happen) in the U.S. I read and highlighted certain parts of her text. How much of what she says about European history, Nazi Germany and Stalin’s Soviet Union in particular, might apply today?

I’m sharing this not because I have all this figured out—far from it. Arendt can prove obtuse and vague at times. And besides, how well has her account of the origins and traits of totalitarianism—and the concept of totalitarianism itself—held up over the last 74 years? My comments following each quote set forth my questions, my responses, and my hypotheses along the lines of what I experienced when I read this text earlier this month. Somebody smarter, more learned, and more ambitious might take it from there. But for now, for what it’s worth, here goes:

The “magic spell” that Hitler cast over his listeners has been acknowledged many times . . . . This fascination—“the strange magnetism that radiated from Hitler in such a compelling manner”—rested indeed “on the fanatical belief of this man in himself” . . . on his pseudo-authoritative judgments about everything under the sun, and on the fact that his opinions—whether they dealt with the harmful effects of smoking or with Napoleon’s policies—could always be fitted into an all-encompassing ideology.

Fascination is a social phenomenon, and the fascination Hitler exercised over his environment must be understood in terms of the particular company he kept. Society is always prone to accept a person offhand for what he pretends to be, so that a crackpot posing as a genius always has a certain chance to be believed. In modern society, with its characteristic lack of discerning judgment, this tendency is strengthened, so that someone who not only holds opinions but also presents them in a tone of unshakable conviction will not so easily forfeit his prestige, no matter how many times he has been demonstrably wrong. Hitler, who knew the modern chaos of opinions from first-hand experience, discovered that the helpless seesawing between various opinions and “the conviction . . . that everything is balderdash” could best be avoided by adhering to one of the many current opinions with “unbending consistency.” The hair-raising arbitrariness of such fanaticism holds great fascination for society because for the duration of the social gathering it is freed from the chaos of opinions that it constantly generates. This “gift” of fascination, however, has only social relevance . . . . To believe that Hitler’s successes were based on his “powers of fascination” is altogether erroneous; with those qualities alone he would have never advanced beyond the role of a prominent figure in the salons.

Arendt, Hannah. The Origins Of Totalitarianism p. 528). HMH Books. Kindle Edition.

I realize that my beginning at the beginning of her chapter takes us straight into talking about Hitler. By deploying the H-bomb right away when discussing Trump, I will raise the hackles of some. I’ll be accused of TDS (Trump Derangement Syndrome) or of crying “Wolf!” again and again when there is no great threat. I readily confess my disdain, my contempt, for Trump, and my conviction about the threat that I believe he presents a dire threat to the well-being—and continuation—of the American republic. You must decide if my arguments and my references to Arendt’s work should have any influence upon your thinking. It’s up to you to discern. With that caveat, let me proceed.

Trump does mesmerize his audiences. I’ve never attempted a Trump rally, but I’ve seen them via TV and video, and they appear to have the tone and aura of a cross between a sports rally and a religious rally. And (to some degree) like typical political rallies. But the feeling tone that I perceive at Trump rallies is exceptional. The fervor of belief is extraordinary. He thrives on these rallies, on the unquestioning adulation that he receives. These surely provide him with an adrenaline high that he craves.

Does he have a “fanatical belief . . . in himself?” Undoubtedly so. One of the key legal issues that he faces and that may daunt prosecutors, is his seeming belief in his own bullshit* and lies. These lies may be delusions, compounded by his continuing loss of mental acuity, itself compounded by his extreme narcissism. But to any hearing him—and wanting deeply to believe him—his belief in himself and all he says is a narcotic that soothes the challenge of knowing and acting in an uncertain world. Arendt refers to “pseudo-authoritative judgments,” but to Trump (by all appearances) and his audience (seeming regardless of appearances), what he utters is The Truth, even if it’s not, or only sort of, so.

Society is always prone to accept a person offhand for what he pretends to be, so that a crackpot posing as a genius always has a certain chance to be believed. In modern society, with its characteristic lack of discerning judgment, this tendency is strengthened, so that someone who not only holds opinions but also presents them in a tone of unshakable conviction will not so easily forfeit his prestige, no matter how many times he has been demonstrably wrong.

This statement needs a bit of parsing. First, Arendt has a particular understanding of how she uses the term “society.” For Arendt, society is contrasted with the “public realm” in which political life is conducted in a democratic polity and the “private realm” of household and family. Society is where we meet with others outside of our private households to share time and talk together. It is the arena where we meet friends and acquaintances. In society, we know one another. She also distinguishes society from “the masses” and “the mob,” terms we’ll dig into later. Thus, in some sense, it would appear from this quote that Arendt is suggesting that the facade of the “crackpot” that she’s addressing is limited to (her definition of) society. But why would this be so? Wouldn’t the phenomena that she’s describing also apply to appearances before the “masses” and “the mob?”

And note that Arendt wrote these observations long, long before the age of social media. She wrote when radio, newspapers, and periodicals were the primary forms of mass communication; television was still in its infancy. Has the internet and social media increased or decreased “the lack of discerning judgment” that Arendt identifies in society? If discernment within society, the masses, or “the mob” (as Arendt defines it) has further declined, how can we ever hope to avoid the demagogue, the “crackpot?”

The hair-raising arbitrariness of such fanaticism holds great fascination for society because for the duration of the social gathering it is freed from the chaos of opinions that it constantly generates. This “gift” of fascination, however, has only social relevance . . . . To believe that Hitler’s successes were based on his “powers of fascination” is altogether erroneous; with those qualities alone he would have never advanced beyond the role of a prominent figure in the salons.

After making the above statement, Arendt fails to identify what “Hitler’s successes” were based upon, how it was “he never would have never advanced beyond the role of a prominent figure in the salons.” (Would not “saloons” or “bars” would have been the more appropriate reference? He was the man of the beer hall putsch.) Nor does she acknowledge that Hitler’s “fascination” was incredibly significant in the political realm (as distinguished from her concept of the public realm). But even if the “social” can disappear when people disburse from a brief congregation, the political realm doesn’t disappear; instead, it has an ongoing aspect via the media. The “salon” may forget about Hitler and his “fascination” when its attendees return home for the night, but not so with the political public, ill-defined as it is.

But if Hitler’s “powers of fascination” were not the key to his success, what were the keys? Arendt doesn’t say here, but one factor seems apparent: a receptive audience. The woes of post-World War I Germany are well-known. What makes contemporary America, or more accurately, a significant chunk of it, susceptible to Trump’s demagoguery? On one hand, there has always been a disgruntled far-right in the U.S. that has been marked by levels of paranoia and conspiracy thinking, such as bers of the John Birch Society. But as I stated above, no other demagogue, even during the Great Depression, gained the presidency and created a formidable, lasting political movement like MAGA. There are many aspects and explanations for this, but I would lump them broadly under the rubric of “the dispossessed;” those whose personal and community well-being have suffered relative or (in many cases) absolute decline over the last several decades. Against this backdrop, there has been an extreme increase in the wealth gap between higher and lower incomes and the perception (largely accurate) that some—mostly in cities and those with more education, and including some minorities and immigrants—have done very well over this same period, thereby breeding a response of anger, resentment, and desire for change—radical change, even at the expense of civility, democracy, and law. These folks are Trump’s audience, his voters; never a majority (so far), but a significantly large number enough to have gotten him elected once and to take over the Republican Party and thereby provide him with a chance to return to the presidency. Trump’s fascinating schtick didn’t fall on barren soil.

It would be a still more serious mistake to forget . . . that the totalitarian regimes, so long as they are in power, and the totalitarian leaders, so long as they are alive, “command and rest upon mass support” up to the end. Hitler’s rise to power was legal in terms of majority rule and neither he nor Stalin could have maintained the leadership of large populations, survived many interior .and exterior crises, and braved the numerous dangers of relentless intra-party struggles if they had not had the confidence of the masses.

[Footnote:] [Hitler’s rise to power] was indeed “the first large revolution in history that was carried out by applying the existing formal code of law at the moment of seizing power” (Hans Frank, Recht und Verwaltung, 1939, p. 8).

Id. pp. 306; 528

Arendt’s observation that even the totalitarian regimes of Hitler and Stalin continued to depend on “mass support” is perhaps surprising and in some ways intriguing. Most people (“the masses?”) go along with political leaders and many don’t even bother the vote, the simplest and most undemanding form of political participation. Leaders of all types, democratic and authoritarian, depend in some measure on the docility of most people. In the U.S., if most people, vocally and actively, spoke up and voted in opposition to Trump and his minions (now essentially all Republican candidates for office), Trump’s would be severely constrained. But most people are docile about this, willing to complain, but mostly unwilling to act in a significant way.

This leads us to Arendt’s second point (quoting Hans Frank): Hitler was democratically elected (under the convoluted Weimar system—which is not to suggest that the U.S. system isn’t convoluted). Hitler and the Nazi Party never received a majority of votes or seats in the Reichstag, and neither did Trump win the popular vote in 2016 when he first gained power. If he’s elected in 2024, it would quite likely be with a minority of the nationwide popular vote. This point should be driven home to those who believe that the 14th Amendment, Section 3—disqualifying anyone from holding office who violated their oath to the Constitution by engaging in an insurrection—should not be applied to Trump because it would be “undemocratic.” This is a weak argument for many reasons, starting with a severe misapprehension of the requirements of a democratic government. Others suggest that Section 3 shouldn’t apply to Trump because Trump’s MAGA followers would react violently. Democracy, the practice of democratic government, requires rules—laws—that define the boundaries and manner of contesting political decisions. If those laws are ignored or violated, democracy will fail. Would-be tyrants and demagogues may get past the voting populace, but those favoring democracy and democratic institutions should never surrender the rules of the game—the Constitution and laws—which a functioning democracy requires,

To be continued . . . .

*I normally try to avoid profanities and scatological language in my public writing (not so much in my private speech), but thanks to the work of the late Princeton University philosopher, Harry Frankfurt and his book, On Bullshit, this barn-yard expletive has risen to the level of a philosophical term of art, and so I justify its use herein.

> But if Hitler’s “powers of fascination” were not the key to his success, what were the keys? Arendt doesn’t say here, but one factor seems apparent: a receptive audience.

Also the principal's interest in *using* his power to serve his own ambitions, no? Here I suppose H. was *more* ambitious than T., although there are people who want to use the latter to serve *their* ambitions