Federalist No. 68

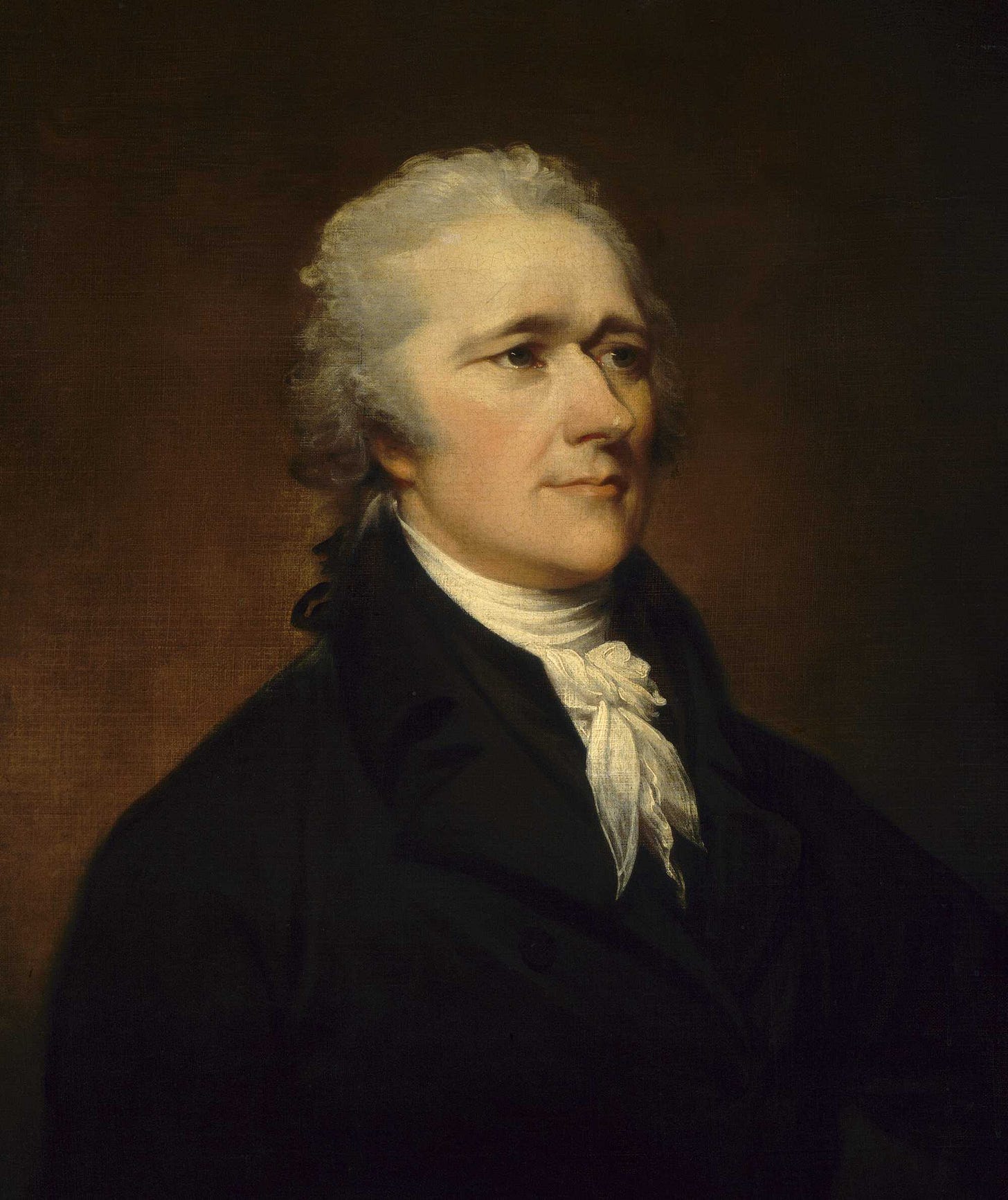

AH on how we elect a president. They foresaw the problem, but their answer failed.

Prefatory Note: I make no effort to hide my admiration, even envy, of the Founders. Therir efforts in designing a Constitution, getting it adopted by 13 quarrelsome states, and then putting it into action was a momentous and fraught set of tasks in which they succeeded. But they were human, and sometimes they got it wrong.

In this particular instance, I’m referring to the Electoral College and their belief that they could avoid “faction” and “party.” Washington could keep Hamilton and Jefferson in the room where it happened, but not for long. By the time of the end of Washington’s tenure as president (eight years), Jefferson and Madison were squaring off against Madison’s fellow Publius, Hamilton, and against Washington’s successor, John Adams. It’s quickly the “Democrat-Republicans” and against the “Federalists.” Try as they might, the Founders could not extinguish “party,” and the constitutional order quietly adopted to the reality of parties.

And so, too, the Electoral College also quickly changed. Why this elaborate system to filter the election of a president? Hamilton tells us exactly why:

It was equally desirable, that the immediate election should be made by men most capable of analyzing the qualities adapted to the station, and acting under circumstances favorable to deliberation, and to a judicious combination of all the reasons and inducements which were proper to govern their choice. A small number of persons, selected by their fellow-citizens from the general mass, will be most likely to possess the information and discernment requisite to such complicated investigations.

It was also peculiarly desirable to afford as little opportunity as possible to tumult and disorder. This evil was not least to be dreaded in the election of a magistrate, who was to have so important an agency in the administration of the government as the President of the United States.

. . . .

Nothing was more to be desired than that every practicable obstacle should be opposed to cabal, intrigue, and corruption. These most deadly adversaries of republican government might naturally have been expected to make their approaches from more than one quarter, but chiefly from the desire in foreign powers to gain an improper ascendant in our councils. How could they better gratify this, than by raising a creature of their own to the chief magistracy of the Union? But the convention have guarded against all danger of this sort, with the most provident and judicious attention. They have not made the appointment of the President to depend on any preexisting bodies of men, who might be tampered with beforehand to prostitute their votes; but they have referred it in the first instance to an immediate act of the people of America, to be exerted in the choice of persons for the temporary and sole purpose of making the appointment. And they have excluded from eligibility to this trust, all those who from situation might be suspected of too great devotion to the President in office.

The process of election affords a moral certainty, that the office of President will never fall to the lot of any man who is not in an eminent degree endowed with the requisite qualifications. Talents for low intrigue, and the little arts of popularity, may alone suffice to elevate a man to the first honors in a single State; but it will require other talents, and a different kind of merit, to establish him in the esteem and confidence of the whole Union, or of so considerable a portion of it as would be necessary to make him a successful candidate for the distinguished office of President of the United States. Though we cannot acquiesce in the political heresy of the poet who says:

"For forms of government let fools contest—That which is best administered is best,"—yet we may safely pronounce, that the true test of a good government is its aptitude and tendency to produce a good administration.

The Electoral College as an independent body of judgment chosen for the occasions of selecting a president didn’t last long. Perhaps it was doomed from the beginning, as I’m inclined to believe. Yet its conception remains important because of the reasons for its creation laid out in this essay. Hamilton foretells the evils that we now experience; he foretold the appearance on the scene of a candidate with “talents for low intrigue, and the little arts of popularity.” And so the electoral system (but not the voters directly) produced such a person in 2016 and could again this year. What’s the cure? I’m not sure. We are clearly in a time when party rises above all, with only a handful of honorable exceptions. And the electorate—or at least a significant portion of it—seems hell-bent on destruction. What would Publius have us do? I don’t believe that Publius would have an answer to this one, it’s too far afield from the hopes, dreams, and plans of their world.

FEDERALIST No. 68. The Mode of Electing the President

From The Independent Journal. Wednesday, March 12, 1788.

HAMILTON To the People of the State of New York:

THE mode of appointment of the Chief Magistrate of the United States is almost the only part of the system, of any consequence, which has escaped without severe censure, or which has received the slightest mark of approbation from its opponents. The most plausible of these, who has appeared in print, has even deigned to admit that the election of the President is pretty well guarded.(1) I venture somewhat further, and hesitate not to affirm, that if the manner of it be not perfect, it is at least excellent. It unites in an eminent degree all the advantages, the union of which was to be wished for.(E1)

It was desirable that the sense of the people should operate in the choice of the person to whom so important a trust was to be confided. This end will be answered by committing the right of making it, not to any preestablished body, but to men chosen by the people for the special purpose, and at the particular conjuncture.

It was equally desirable, that the immediate election should be made by men most capable of analyzing the qualities adapted to the station, and acting under circumstances favorable to deliberation, and to a judicious combination of all the reasons and inducements which were proper to govern their choice. A small number of persons, selected by their fellow-citizens from the general mass, will be most likely to possess the information and discernment requisite to such complicated investigations.

It was also peculiarly desirable to afford as little opportunity as possible to tumult and disorder. This evil was not least to be dreaded in the election of a magistrate, who was to have so important an agency in the administration of the government as the President of the United States. But the precautions which have been so happily concerted in the system under consideration, promise an effectual security against this mischief. The choice of SEVERAL, to form an intermediate body of electors, will be much less apt to convulse the community with any extraordinary or violent movements, than the choice of ONE who was himself to be the final object of the public wishes.

. . . .

Nothing was more to be desired than that every practicable obstacle should be opposed to cabal, intrigue, and corruption. These most deadly adversaries of republican government might naturally have been expected to make their approaches from more than one quarter, but chiefly from the desire in foreign powers to gain an improper ascendant in our councils. How could they better gratify this, than by raising a creature of their own to the chief magistracy of the Union? But the convention have guarded against all danger of this sort, with the most provident and judicious attention. They have not made the appointment of the President to depend on any preexisting bodies of men, who might be tampered with beforehand to prostitute their votes; but they have referred it in the first instance to an immediate act of the people of America, to be exerted in the choice of persons for the temporary and sole purpose of making the appointment. And they have excluded from eligibility to this trust, all those who from situation might be suspected of too great devotion to the President in office.

. . . .

The process of election affords a moral certainty, that the office of President will never fall to the lot of any man who is not in an eminent degree endowed with the requisite qualifications. Talents for low intrigue, and the little arts of popularity, may alone suffice to elevate a man to the first honors in a single State; but it will require other talents, and a different kind of merit, to establish him in the esteem and confidence of the whole Union, or of so considerable a portion of it as would be necessary to make him a successful candidate for the distinguished office of President of the United States. It will not be too strong to say, that there will be a constant probability of seeing the station filled by characters pre-eminent for ability and virtue. And this will be thought no inconsiderable recommendation of the Constitution, by those who are able to estimate the share which the executive in every government must necessarily have in its good or ill administration. Though we cannot acquiesce in the political heresy of the poet who says:

"For forms of government let fools contest—That which is best administered is best,"—yet we may safely pronounce, that the true test of a good government is its aptitude and tendency to produce a good administration.

. . . .

PUBLIUS