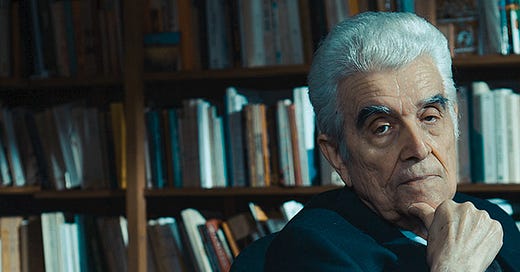

I’ve been circling around the thought of Rene Girard (1923-2015) for over a decade now, like a vulture, fearful that the prey might not be ready for the picking, that it might bite back. Or to put it more prosaically, I might be attempting to bite off more than I can chew. But my gnawing desire to understand myself and my fellow humans—especially in this turbulent age, where we, as a species, seem to be headed deeper into a time of troubles—led me to commit to overcoming my reticence. I ordered and received a copy of Girard’s first book, Deceit, Desire and the Novel: Self and Other in Literary Structure (1961/English translation 1966). And while I was at it, I decided to check out what a local library had available. In my search, I discovered this book. I’m glad I did. Perhaps, it might be argued, that I should ignore the individual author and the particulars of his entire life, but Haven’s book goes beyond a mere academic study of Girard’s work and beyond a mere recitation of the facts of Girard’s life. R.G. Collingwood, in writing his autobiography, argued that “the autobiography of a man whose business is thinking should be the story of his thought. I have written this book to tell what I think worth telling about the story of mine.” Autobiography, vii. The justification of a biography of a person of thought should be no different; what interests us most should be the genesis of the subject’s thought and how the circumstances of the subject’s life relate to that thought. Of course, different subjects and different biographers will draw those lines differently, with more or less finesse and justification, but in any event, Cynthia Haven’s choices in this regard strike me as exemplary.

One advantage Haven enjoyed in writing this biography was her personal acquaintance with Girard. Although not a tenured academic herself, she lived and worked around (and for) Stanford University, and came to know and befriend Girard late in his life. Thus, with the aid of Girard’s wife and family, as well as directly from Girard, she was able to recreate the life and career of this extraordinary thinker. Indeed, Girard didn’t follow a traditional trajectory in his life or career. Girard was born and raised in Avignon, France, and trained in Paris at a school for “chartists,” to wit, an archivist, like his father. But after the war (Girard was just young enough to avoid service), he emigrated to the U.S., where obtained a Ph.D. in history from Indiana University. And there, because of demand, he ended up in the French Department, and remained a member of the French, Romance, or English language departments at the subsequent universities he taught at. But after the publication of his first book, he broke the bounds of literature to make the whole of human relations as his subject of study, not just literature. Having become a literary scholar, he realized the reality of what he dubbed “mimetic desire” not only in literature, but in human life. From this still early point in his career, human life as it is shaped by mimetic desire becomes his big idea that he continues to unpack through the remainder of his life, through the arenas not only of literature, but also anthropology, religion, sociology, politics, philosophy, and history. In Isaiah Berlin’s nomenclature, Girard was a hedgehog, he held one big idea; but in developing that big idea, he was a fox, continually exploring different fields, oblivious to academic boundaries. (And you can no doubt imagine that those more concerned with academic boundaries would attempt to shoo Girard away when he came sniffing around their fields—to no avail.

In addition to detailing the story of the unfolding of Girard’s big idea, Haven also provides an appreciation of the man and his work. If Haven is to believed—and I’ve not reason to doubt her—Girard was a dynamic but charming man. His personal life appears to have been content and unremarkable; his marriage extended 64 years, to the time of his death in 2015. But his ideas? They remained relatively little known and appreciated until later in his life, but it seems, they have begun to gain a wider readership since the time of his death. This might be in part because of the enthusiasm for his ideas expressed by the Silicon entrepreneur and Trumpist, Peter Thiel. (How Thiel reconciles his expressed admiration for Girard—and Thiel has put his money where is mouth is—and his support of Trumpism, remains a mystery to me. Trump is the incarnation of an individual with unchecked desire who promotes rivalry, scapegoating, and violence—that which Girard’s project seeks to ameliorate and perhaps even overcome.)

We should note at this point that one reason why some have shied away from Girard’s work is because of its specifically religious implications. Girard was raised in a nominally Catholic family (at least on his mother’s side), but as a young adult he stepped away from any practice that he’d inherited. But then in the late 1950s, he underwent an epiphany of sorts and returned to Catholicism. The event is not well specified by Haven, but then I suspect that Girard didn’t provide much in the way of specifics. And all of this might conversion experience might not even have been remarked upon in passing except that in 1978 Girard published a further and relatively complete exposition of his insight in the work later translated and published in English translation in 1987 as Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World. In this work, Girard’s insights take a specifically Christian turn. One of the insights of the theory of mimetic desire is that these desires create rivalries that in turn create social unrest. To alleviate social unrest, societies turn to scapegoats, often individuals on the margins of society who are seen as common enemy and source of the social unrest. Girard argues that the story of the passion and death of Jesus is a scapegoat story, but that the innocence of the victim is manifest and therefore can serve to break the scapegoat mechanism. In fact, I may have first come across Giard’s when I read Princeton philosopher Mark Johnston’s Saving God: Religion After Idolatry (2009) (with further references here and here). I’ve also seen Girard discussed by philosopher Roger Scruton and polymath Garry Wills, among others. Do I think then that Girard is a "religious writer?” No, at least not in the sense that one must be a Christian or in any sense religious to appreciate (and acknowledge) what Girard’s thesis suggests. If Girard is correct that mimetic desire is a fundamental fact of human relationships (society), then whether Christianity (or any other religion) effectively deals with this dilemma is up for grabs.

This book was a pleasure to read. Do I conclude that I know all about Girard and all that he says and implies? No! But it does serve as an aperitif, and it has stimulated my desire (mimetic?) to work through the main course, which will be a long, slow feast to consume and savor.